Welcome to our five-part series on how to decide where to donate effectively. We’re going to go on an in-depth journey through the psychology of donations, the best ways to tell whether a charity is good at what they do, and how to actually give most effectively.

- What drives donations

- Choosing a cause to support

- Good ways to choose a charity

- Bad ways to assess charities

- The best ways to give

In our last post, we talked about some key metrics you can use to find a charity that is likely to make a strong impact with your donation.

But there are other ways that people use to decide which charity to donate to. These are the metrics that we don’t recommend, and why.

What is a charity?

Many of the worst offenders for charity metrics are based off a fundamentally poor understanding of what charities do and are.

Charities exist to make change to the world. What this looks like depends on the cause they are attempting to solve, but in general they take in money (from donations, government grants, or delivering services) and spend that money in the way they think will best improve the cause. Any money not spent is saved for the future. This all seems rather obvious, but it’s important to start with this fundamental premise.

The overhead ratio

You’ve probably heard of the idea that charities that spend less on overheads are ‘better’. It’s one of those pernicious ideas that’s wormed its way into the collective wisdom and is very hard to kill.

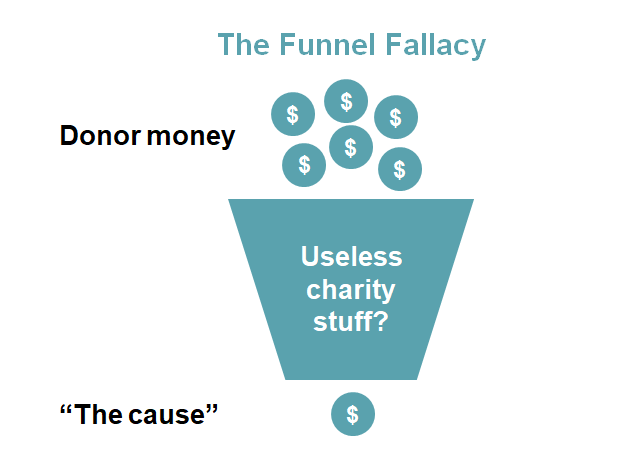

The basic argument goes like this: I want as much of the money I donate to be spent on the cause. Overheads are money that charities don’t spend directly on the cause. Therefore, charities that have the lowest overheads are the best to give to.

The intention is the right one, but the problem is that it’s wrong. Entirely, completely wrong.

What is an overhead? It’s easy to think of overheads as ‘waste’ but they’re not even remotely equivalent. Overheads are things like:

- Auditors and accountants

- Legal advice

- Training

- Providing services (e.g. running a shop)

- Technology

- Measuring and evaluating whether their programs are having an impact

None of the above is waste, especially if you are interested in charities being effective with the dollars they spend.

There are many reasons for different charities having different levels of overheads. Some ways of affecting a cause are more ‘admin-heavy’ than others. To take a spurious example, say there are two charities that want to encourage kids to read. One of them coordinates reading groups at local libraries, which requires a lot of administrative effort to contact the libraries, promote the programs, schedule the groups, and so forth. The other charity just sends people randomly out into the street to shout ‘YOU SHOULD BE READING’ at passing children.

The second charity, YellingForReading, would have a significantly lower overhead ratio. Every dollar you give them is spent directly on having people out there yelling at kids. That doesn’t mean they’re being more effective at actually improving literacy levels.

Photo by Moose Photos from Pexels

For you to believe that the overhead ratio is a good way to decide which charity is doing well, you need to assume:

- There is no value in having an effective organisation

- The way of affecting a cause that needs the least staff is always the best

- Measurement and evaluation are a waste of money

I would argue that all of the above are false.

I’m not saying that there’s no good way to tell charities apart (that’s what the last article was about). It’s not that more overheads are actually good. It’s that there’s no correlation between how much good a charity is doing and its overheads [act_tooltip title='(1)’ content=’See https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4179876/‘]. They’re almost completely unrelated. Indeed, there’s some evidence to suggest that good charities spend more on administration [act_tooltip title='(2)’ content=’https://giving-evidence.com/2013/05/02/admin-data/‘].

This is important, because we don’t want to see what happened in the USA repeat itself in Australia.

What happens when donors make decisions based on the overhead ratio

America has a rather different charity sector to Australia, with a significant amount more personal philanthropy. For whatever reason, the myth of the overhead ratio put down its roots there in a very significant way, leading to what the Stanford Social Innovation Review called the “Nonprofit starvation cycle”. Charities were trying to spend so little on overhead it was actually making them less effective as organisations. It was even jeopardising their very existence.

The cycle is described like this:

“The first step in the cycle is funders’ unrealistic expectations about how much it costs to run a nonprofit. At the second step, nonprofits feel pressure to conform to funders’ unrealistic expectations. At the third step, nonprofits respond to this pressure in two ways: They spend too little on overhead, and they underreport their expenditures on tax forms and in fundraising materials. This underspending and underreporting in turn perpetuates funders’ unrealistic expectations. Over time, funders expect grantees to do more and more with less and less—a cycle that slowly starves nonprofits.”

Stanford Social Innovation Review

This got so bad that three of the largest charity-rating organisations in the US banded together to counter what they called the “overhead myth”. You can read their open letter to donors here. http://overheadmyth.com/

If you’re still not convinced, I’d highly recommend this TED talk by Dan Pallotta entitled “The way we think about charity is dead wrong”.

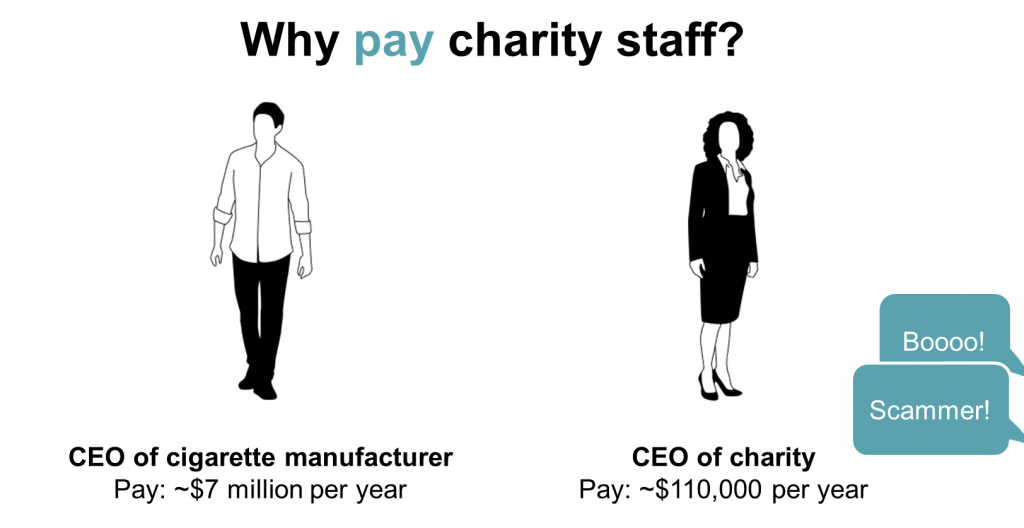

Why pay charity staff?

Another bad metric is to ask how much charities pay their staff, especially their CEOs. This is a tricky one, because it’s a bit less cut-and-dried than the overhead ratio.

But we’ll start at the easy part – why charities need paid staff at all. There remain people that are sceptical about charities needing to pay staff. Why do people not just do it out of the goodness of their hearts? Surely there’s enough volunteer labour to go around. And there’s a grain of truth to this – a huge number of smaller charities (ones with only a few people) are run entirely by volunteers.

And yet charities are organisations like any other. And organisations take time and effort to lead and control. The Red Cross, for example, has a revenue of over $900 million and hundreds of staff. It is, objectively, a large and complex organisation doing important work. There is absolutely no doubt that it needs staff with extensive experience working full-time to keep it operating.

There’s a more fundamental question at play here – wouldn’t you want the charity to be using the best staff it can? Volunteers are essential, the backbone of the charity industry. But there are tasks that it would be simply unreasonable to expect a volunteer to do, and the charity will get far better results by paying someone skilled to do them.

As to what CEOs should be paid, there’s complexity here. Charities operate out of the same job market that for-profit organisations do (except, perhaps, slightly more rarefied). If we assume that a good CEO will lead to a more impactful charity than a bad CEO, then it is in a charity’s best interests to get a good CEO. Yet CEO pay in the private sector has, for a variety of reasons, shot up far above previous milestones over the last few decades. And while charity CEOs are generally paid a deep discount compared to their private sector colleagues, they are still swimming in a similar pond.

From another perspective, the way our society values different forms of labour is difficult to comprehend. The average pay of the CEO of a cigarette manufacturer is (very roughly) about $7m. The corresponding average pay of a charity CEO is about $110,000. One of these people is devoting their life to attempting to improve the world, the other one is selling an addictive product that kills people. It’s perverse.

All told, while charities should be able to justify the pay their senior management receive, it should by no means be considered a black mark to pay them well. Being able to offer competitive rates means that a charity can get high-quality employees and create more impact. Hobbling a charity by insisting it pays far less than its employees are worth (or, as some think, not at all) just means you are decreasing the likelihood that it will be a success.

Charities (mostly) spend their money wisely

A lot of negative media coverage comes down to shaming charities for spending their money ‘wrong’. This is also at the heart of the overhead myth – the lack of trust that the charity is using your hard-earned money wisely. At a purely emotional level this is understandable. Nobody wants to think that the money they gave to a charity for starving orphans was actually spent on an office chair rather than food, even though chairs are quite important for the staff to do their job saving orphans.

At the root of it is a question of trust. We’ve been taught, by the media and by society at large, to be cautious and careful and suspicious of people asking for money. Indeed, Our trust and confidence in Australian charities is declining, with now only 20% of people agreeing that most charities are trustworthy. (2017 ACNC report). There’s a perception that there’s no end of scammers and ne’er-do-wells out there. And it’s true, if you give your money to every poor starving Nigerian prince who sent you a nice email, you may not get the social impact you were hoping for.

But the ability to trust that a charity is capable of deciding how best to spend the money you give it is important. To believe in the overhead ratio is to believe that you know, better than the charity does, the best way to spend funds on the cause they exist to fight. Charities are organisations built to serve a purpose, to fulfil a need. They are filled with passionate people trying to solve that need.

This may sound a bit rich, coming from a charity assessment website. And yet none of this is to say that some charities are not better than others. They are – that was the point of the last article. It’s just that using the overhead ratio or their staff costs are terrible ways to tell whether a charity is better than another. All the other methods are harder, and more time-consuming, or involve the charity spending money on measuring their impact. This is why the overhead ratio is so pervasive – it’s seductively simple. It takes a complex idea and reduces it down to a single, simple (but ultimately wrong) number.